Blindly following any training plan is not the way to go

Revere Greist

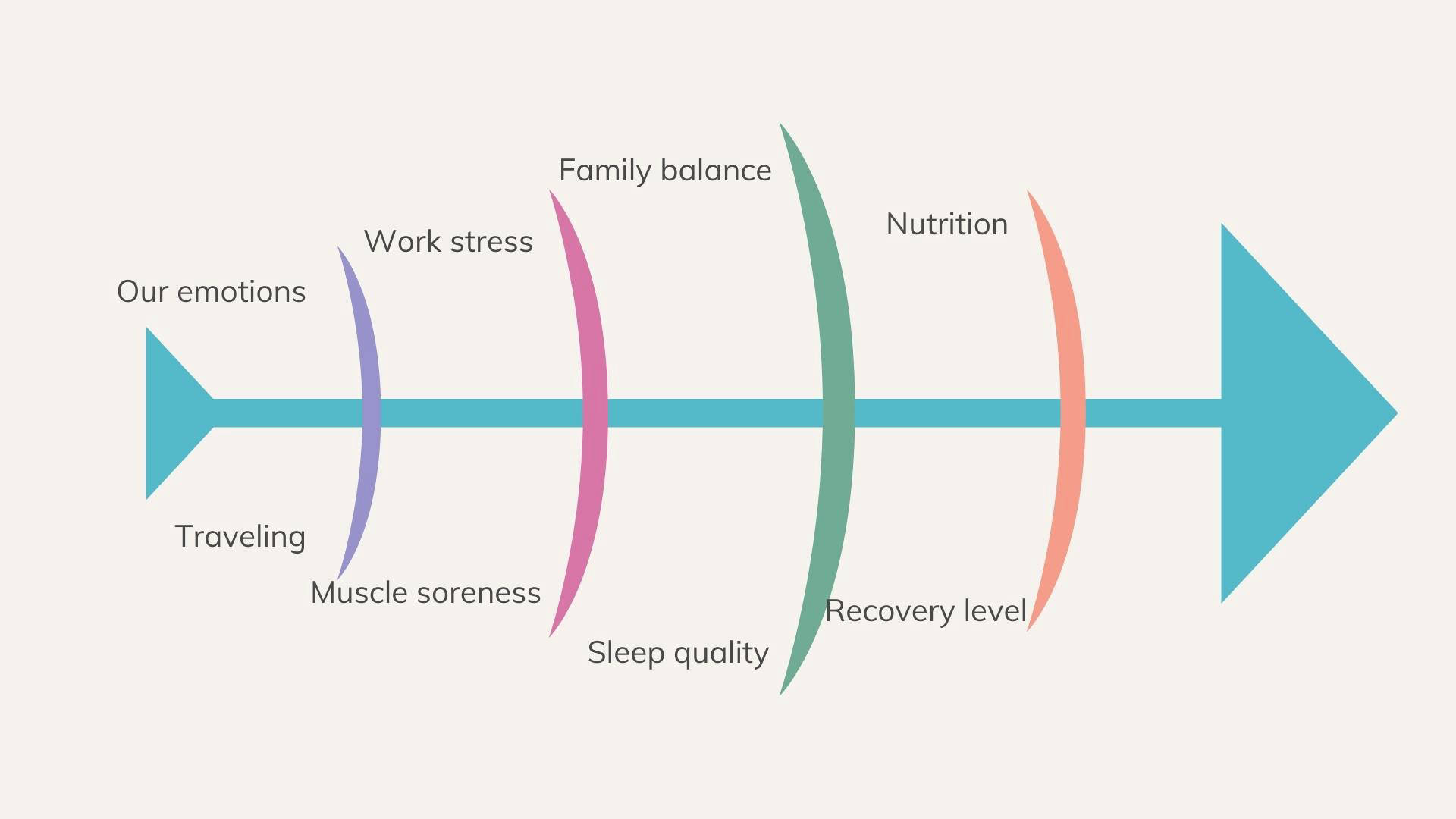

We are unable to 100% predict our body's reaction to training load load because we do not live in a vacuum and our training takes place in the context of real life: our emotions, work and other everyday things. For amateur athletes, these factors can be even more pronounced, since the number of external factors affecting our bodies and minds can be even more than for professionals.

Strict adherence to a training plan sounds like a great idea in theory but produces a desired outcome only in one case - when adaptation to training follows a predictable path. Indeed, athletes and coaches are often obsessed with planning for upcoming workouts because they understand the dose-response relationship with increased training. They carefully consider what must be done in order to achieve the development of the athletic qualities we require to succeed in races. However, the best laid plans sometimes go awry, and we have to make adjustments.

The basis for the traditional coaching philosophy is that if you balance adequate training load and recovery, then results in competition should follow. Of course, there are cases when all of your coach’s assumptions and plans are put into practice, but something goes wrong and you can’t manage your next scheduled workout. When this happens – and we’ve all been there – we have thoughts that perhaps training stress was too high, we did not have enough time to recover from previous workouts, other life factors were intruding, and so on.

These other factors can play an important role, one that has been documented in sports science research. Scientists have studied the relationship between the amount of training stress and increased athletic performance in amateur athletes. In one research study, one group of athletes was isolated from everyday stresses, while another was allowed to be subjected to them.

Which group achieved the greatest increase in athletic capacity during the two weeks of the experiment? You guessed it. The athletes without stress achieved significant improvements in performance while the stressed group didn’t show any progress.

This research once again confirms the fact that, when planning training, it is always necessary to take into account the influence of external factors, such as sleep quality, nutrition, the level of home and work stress, and so on.

In Zihi you can enter this information daily and the system will take it into account to generate a truly adaptive training plan for you. If you enter information about these external factors every day, Zihi is more able to create a training plan that is customized to you.

Here’s what regular athlete who are not using Zihi or training with a coach can do to accommodate life stress in practice:

- Always pay attention to what’s happening in your life outside of training. This isn't so easy, because we experience emotional stress on a daily basis. Timely adjustment of your training plan will help you to avoid overload and overtraining.

- To individualize the load as much as possible. We should not all use the same training plans, as many “off the shelf” training plans would suggest. . You need to rebuild and adapt this plan for yourself. Each of us has our own personal “adaptive reservoir,” and the capacity of each person’s reservoir is different. Each athlete must determine the amount of training load that he or she is able to manage. The simplest test for determining under-recovery is the orthostatic test with heart rate measurement we have already considered.

- When facing a block of strenuous training, it is desirable to minimize external stresses. This does not mean that you need to lead a monastic lifestyle, but avoid stressful situations as much as possible.

- If, for one reason or another, you don’t meet the goals of your training plan and you did not achieve your desired result, you should remember that this is a small price to pay, and that you’ll have other chances at it. There are situations when decision-inflexible athletes ignore the reality around them and follow a long-term plan with fanatical devotion. The penalty for this approach can be much more serious than just not having a personal record. This kind of behavior can also lead to the most dangerous type of overtraining - the parasympathetic type - from which recovery can take up to six months.

There should always be a plan, but how much we should stick to it depends on external circumstances as much as on your response to the load.

About the author

Revere Greist

Revere Greist is the COO and Co-Founder of Zihi, AI-based endurance sports training platform. With more than 20 years in endurance sports and Kona AG 8th place he is fond of sport science and the most effective ways to be fit for a race.

MBA, COO

Madison, WI